Something feels off, and users are struggling to describe it.

Across Reddit and developer forums, the complaints have a familiar rhythm. Responses feel slower. Reasoning feels thinner. Models forget instructions mid-conversation. Hallucinations creep into tasks that once felt routine. Paying subscribers wonder why the free tier feels indistinguishable from Pro. Longtime users threaten to switch to Gemini or Claude out of fatigue and frustration.

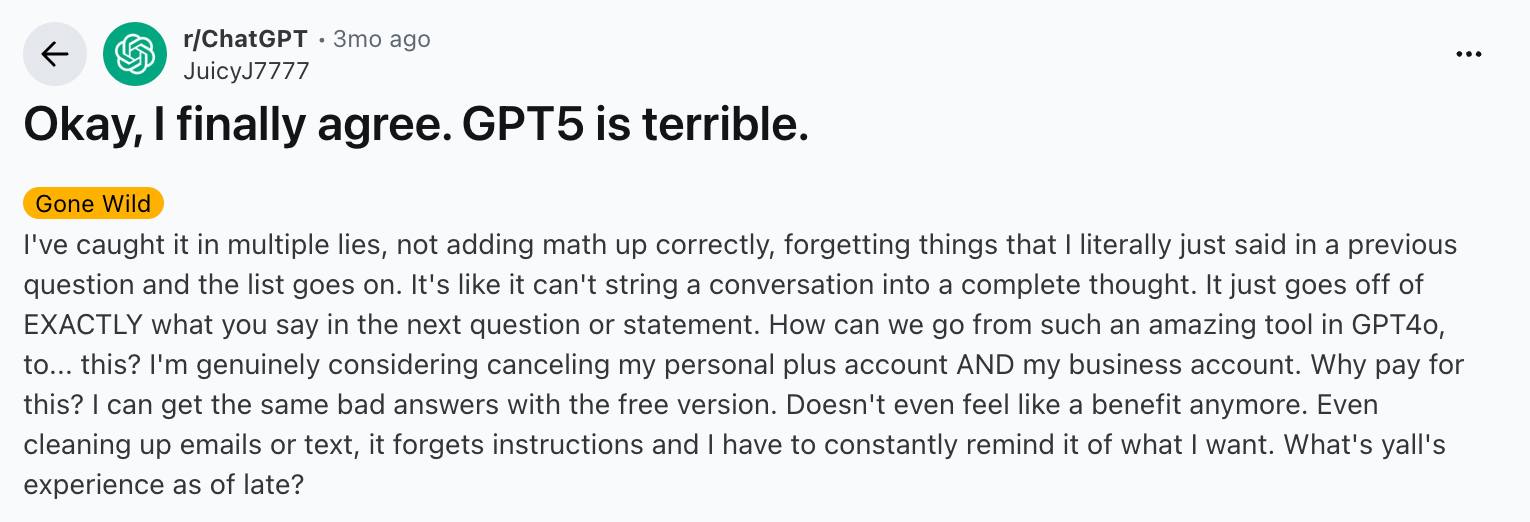

One user describes GPT “getting dumb” overnight. Another reports browser crashes and nonsensical repetition after months of reliable performance. Others describe GPT-5 as colder, less coherent, and oddly literal, unable to hold a conversational thread across turns. On the surface these read like isolated bug reports. But collective intuition indicates that something fundamental has changed.

There is no single smoking gun here. Much of this evidence is anecdotal. Yet the volume, consistency, and persistence of the sentiment matters. When thousands of power users independently converge on the same conclusion, it becomes a signal worth interrogating.

What users are reacting to has a name.

Enshittification

“Enshittification” is a term coined by Cory Doctorow to describe a recurring pattern in platform businesses. To quote Doctorow:

“Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die. I call this enshittification, and it is a seemingly inevitable consequence arising from the combination of the ease of changing how a platform allocates value, combined with the nature of a "two-sided market", where a platform sits between buyers and sellers, hold each hostage to the other, raking off an ever-larger share of the value that passes between them.”

“But Nick,” you say, “how is ChatGPT a two-sided market? I interact with the platform and it responds to me? There aren’t any ads!”

There aren’t any ads… yet.

We are entering Phase 2: Once users are locked in, the platform starts adding more ads, exploiting user data, and prioritizing business clients and advertisers, over consumer users to generate revenue (think Amazon Prime ads, or ads on social media platforms).

After numerous reports and leaks, OpenAI has finally confirmed that ads are being tested in ChatGPT. They will appear at the bottom of responses in the free tier and its lowest-cost paid plan, ChatGPT Go, while higher-priced subscriptions remain ad-free. Ads will be clearly labeled, will not influence responses, and will not appear in sensitive categories such as politics or mental health, for now…

That could be an article on its own, so let’s instead focus on the other core drivers of Phase 2: profit-driven decay (prioritizing profit over user value) and platform decay (a worsening of quality, functionality, and user experience over time).

Uber is an easy to understand and classic example of both. Early Uber offered clean cars, low prices, fast pickups, and polite drivers. It disrupted the private hire market by prioritizing user experience above all else and subsidising prices by using venture funds to keep user costs artificially low. Once market share was secured, prices soared, service quality became inconsistent, and drivers absorbed more risk while earning less. The app still worked, but the magic was gone.

Enshittification is an economic transition and a hallmark of venture-backed products. Eventually platforms shift from rapid growth to extraction under pressure from scale, cost, and expectations.

From miracle to mass utility

At peak hype, ChatGPT felt miraculous. GPT astonished users with reasoning, creativity, and context handling that felt qualitatively new. OpenAI priced aggressively, subsidizing the cost of compute, and focusing on winning mindshare. The goal was dominance.

It worked.

Today, ChatGPT has over 800M weekly active users and receives around one billion queries per day. It is one of the most widely used software products on the planet and one of the top five most-visited websites worldwide. It runs across countless browsers, phones, enterprise workflows, and education systems. But that scale translates directly into electricity, water, chips, and data centers.

Large language models are expensive to run. Every token generated requires matrix multiplications across billions of parameters. Even marginal improvements in efficiency translate into enormous cost savings at global scale. When usage explodes, optimization stops being optional.

Why OpenAI has to change the product

Once a platform operates at a global scale, the incentives invert. Reliability, efficiency and predictability matter more than personality or brilliance.

OpenAI now operates under several simultaneous constraints, and each one directly shapes how the product behaves in practice. Users experience these changes as “dumbing down,” even while engineers describe them as optimization. So what are they really doing?

The first is compute scarcity. High-end GPUs remain supply constrained and expensive, and running full-precision frontier models for every casual prompt is not economically viable. In response, OpenAI increasingly relies on quantization. Quantization reduces the numerical precision of a model’s internal calculations, for example moving from 32-bit floating point numbers to 8-bit integers. In the simplest terms, think of it as writing numbers with fewer digits. Instead of working with numbers as long as the alphabet, the model works with numbers closer to eight digits long. It’s similar to how we cap money at two decimal places. You reduce the size of the calculation and speed it up with minimal loss of accuracy. The benefit is large models run on smaller devices, lower memory usage, reduced energy consumption, and dramatically lower cost. But the tradeoff is subtle but real. Small rounding errors accumulate, especially in long chains of reasoning, and answers can feel less sharp or less stable over time.

Second, energy and sustainability pressure. Research from UCL and UNESCO shows that practical optimizations such as shorter responses, lower numerical precision, and smaller task-specific models can reduce energy consumption by up to 90 percent without large accuracy losses. At one billion queries per day, those savings are existential. This is why response length is increasingly constrained. Shorter outputs use dramatically less energy. However, responses can feel terse, compressed, or lacking nuance, even when the underlying capability has not disappeared.

Third, misuse and regulatory risk. As models become more capable, they also become more dangerous. Guardrails, refusal layers, and content filters add overhead and friction, both computational and experiential. Guardrails add their own effects. Safety layers can interrupt reasoning chains, suppress exploratory answers, or push responses toward safer, more generic phrasing.

Fourth, product simplification. Mass-market products cannot expose every knob and switch to users. Instead of letting users choose models explicitly, OpenAI increasingly relies on automatic routing, quietly selecting cheaper or smaller models for many tasks based on perceived complexity. Users may not even be aware which model answered their question, only that the tone, depth, or reasoning quality feels inconsistent across sessions.

This is how degradation shows up in practice. Individually, Open AI would argue that all of these changes are defensible. Collectively, they alter the texture of the product.

Why benchmarks do not settle the debate

OpenAI can reasonably argue that benchmarks show progress. New models score higher on standardized tests. Bugs get fixed. Sycophancy issues are acknowledged and rolled back. Some early GPT-5 complaints were linked to a faulty auto-switcher.

However, benchmarks fail to measure the erosion of trust. Power users notice when a tool stops feeling sharp or when they have to repeat instructions. These experiences do not always register in aggregate metrics.

This gap between measured performance and perceived quality is where enshittification thrives. It’s the difference between what they report publicly and what you as the user feel and experience.

A shift in identity

OpenAI likes to market itself to investors like a research lab. But it is a consumer platform operating at a massive scale. That shift changes what success looks like.

For a research lab, excellence is pushing the frontier. For a platform, excellence is uptime, cost control, safety, and consistency for the average user. These goals are not aligned.

As OpenAI optimizes for mass adoption, users will feel abandoned. Especially the ones who arrived early and built workflows around peak performance that were never economically sustainable.

Let’s be clear. Is OpenAI intentionally destroying its models to save money? There is no hard evidence for that claim. But there is strong evidence that OpenAI is aggressively optimizing its systems under real constraints.

The reality is that the outcome feels the same to users.

Whether OpenAI can arrest the slide, segment experiences, or reintroduce excellence without breaking the economics remains an open question. History suggests this phase rarely reverses itself without competition forcing change.

For now, the diagnosis is simple. The enshittification has begun. And what comes next?

Ads.